Tracing The Shape 21: The Grave

Michael Myers came back to Haddonfield with a plan.

It may not have been a complete plan, and it may have depended in no small part on the obliviousness of those around him, but he knew what he wanted to do when he got home. And we know this because of the gravestone.

We don't see Michael stealing his sister's headstone, yanking it up out of the cemetery, heaving it into his station wagon, and driving away. But we know he did it. It's one of those details the movie brings up with a beautifully chilling scene with Loomis in the cemetery, then simply drops until Laurie Strode finally makes it across the street.

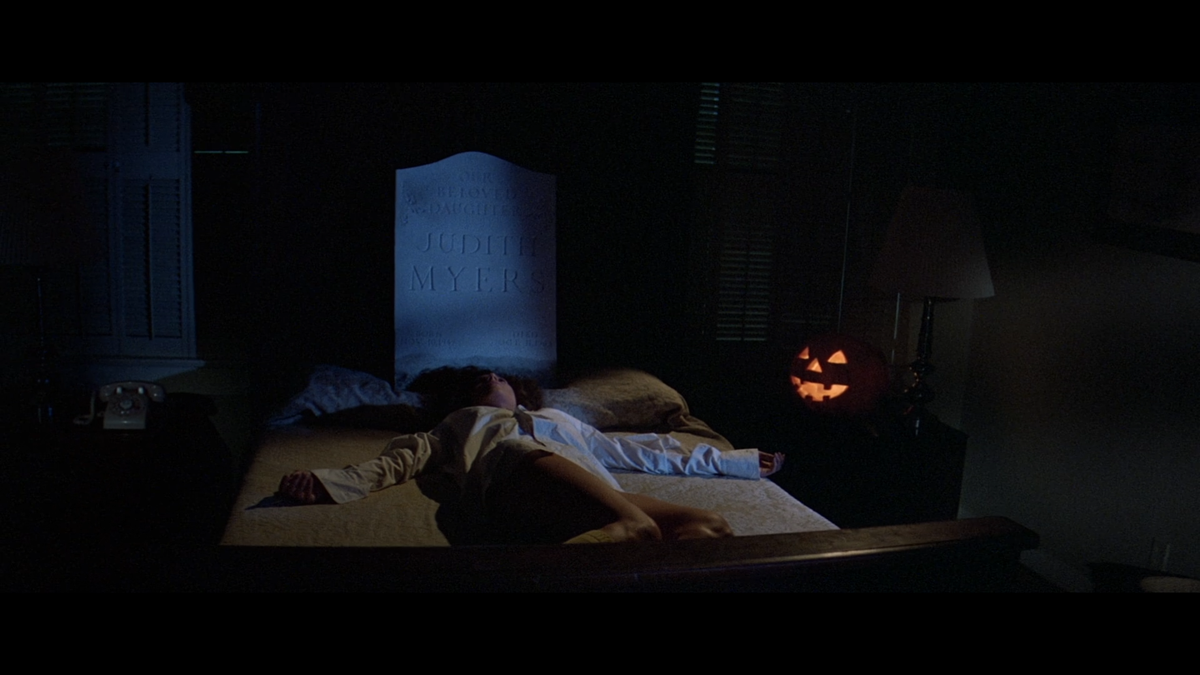

What she finds, after noticing a lone light flickering under a door upstairs in the Wallace house, is her best friend splayed on the bed, jack-o'-lantern beside her, headstone above her head, open eyes staring at the ceiling. It's one of horror's great tableaus, a haunting image that adds weight to the slaughter of innocents running through Halloween, because it feels like something out of a folk-horror film, not a slasher. A megalith on the big screen. A sacrifice.

And maybe it is.

It's here that we must once again turn to the eternal question: What does Michael Myers want? We know that he went to retrieve this headstone in broad daylight, and hauled it around in the back of his car until he found the right moment to use it. Killing Annie in her car was a smart move, just like waiting for Lynda and Bob to split up was a smart move, just like luring Laurie across the street into a dark house was a smart move. But what is this?

If you're trying to creep under the radar, lugging around a massive gravestone in broad daylight, then hauling it out of your car on Halloween night (which we don't see but which clearly happened at some point), is not a smart move. It's not an easy move, even with Michael's strength. It's also not a murder weapon, though it's easy to imagine certain ways in which it could have been. So why do it?

For that we have to go back to one of my earliest theses in this essay series, which is that the long flashback which opens the film is not simply a flashback, but a replay of Michael's memory of his last night of freedom. He has distilled the murder of his sister down into a perfectly contained sequence of dreamlike, floating movement and quick, bloody brutality, cut off only when his parents rip away his clown mask. He has this memory constantly circling his brain like a satellite, always coming back around to the front of his mind, always refining. It's the defining moment of his life, and in pursuing other misbehaving babysitters like his sister in 1978, it's clear he wants to relive it.

But it's also clear that part of him is clinging not just to the act of killing, but to Judith Myers herself. We don't get very many clues about their prior relationship, but Judith is a teenager and Michael is six, no longer a cute little toddler and now a nosy little boy who anchors his big sister to their home. She's a babysitter because of him, she's stuck at home because of him. It is easy to imagine a life Michael faintly remembers when his sister was kinder to him, and whether he intended to kill her or not, it's clear she's not that person for him anymore by the time the knife comes down.

After that, a life-changing moment that estranged him from his parents, his community, any hope of a normal life, Michael was never the same. I think it's because he got a taste of something beyond the life he knew and couldn't come back from it, sure, but I also think it's because he never got closure with Judith. Any mourning he could do, if he can mourn, was done privately. He was cut away from the rest of his family. His parents might not have ever looked him in the eye again.

He wants that gravestone because it's a reminder of what he left behind, the literal marker in the dirt where his life twisted forever. I don't know if Michael is capable of regretting anything, and even if he is, I don't think he regrets killing Judith. What I do think is that Michael is picking up in Haddonfield right where he left off, in a symbolic, ritualistic way. He chose Annie for this honor because she might remind him of Judith the most – after all, she's the one who mouthed off at him and called him names. He also chose Annie because he saw firsthand how close Annie was to Laurie.

Which brings us to the real crux of the scene, the point when it becomes something more than Michael making a symbolic point about his return to Haddonfield. He knew exactly what he was doing when he turned on those lights, just for a moment, to catch Laurie's eye. He knew what he was doing when he let the phone ring after hanging it up. He knows what he's doing when Laurie slips through the back door of the Wallace house and he puts a rake against the handle so she can't get back out. And he most definitely knows what he's doing when he stages Annie, Bob, and Lynda in the same room for Laurie to find.

Bob and Lynda are jump scares, but Annie is a message. Annie is Michael's way of telling Laurie that, monster though he is, in his own horrifying way he is capable of honor, even of love. Does he love her? He's certainly obsessed with her. Love might be too strong a word, but there is a feeling there, an intensity of expression that required him to make something for her and her alone. Whatever else he intended to do with that gravestone, he now intends Laurie to be the one to find it, and what he's placed under it like a Christmas present.

Because she's special. And she's about to give him the fight of his life.

Next Time: The Chase!